Last year was shaped by events that barely anyone predicted – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, horrendous floods in Pakistan and a hard-fought breakthrough on finance for victims of climate disaster.

So instead of making predictions, we’re posing 13 questions that will define the world’s climate response in 2023. The answers mostly depend on the decisions powerful politicians make at home in their capitals and on how their diplomats negotiate at international meetings – at the World Bank and the IMF, at Cop28 and at the International Maritime Organization.

People have power too. Last year, climate laggards Scott Morrison of Australia and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil were booted out of office. This year is relatively quiet for major elections but wise politicians will note that climate is increasingly salient to voters.

1. Will World Bank and IMF move the big bucks to climate?

Since the end of the second world war, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have governed the global financial system. Both are based in the US and controlled by the US government and its allies.

Last year, the prime minister of climate-vulnerable Barbados, Mia Mottley, began a push to mobilise these organisations in the fight against climate change. At both organisations’ annual meetings in October, the US and the rest of the G7 backed the broad thrust of Mottley’s proposals.

So some reform is all but inevitable. At this year’s spring meetings of both institutions in Washington DC on April 10 to April 16 and then their October annual meetings, we will find out how far these reforms will go.

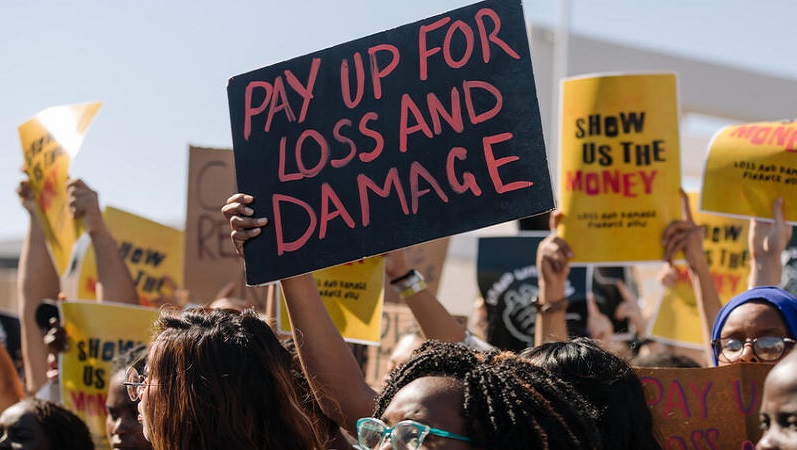

2. Who will pay and who will get loss and damage funds?

At Cop27, governments agreed to set up a “loss and damage” fund for victims of disasters caused by climate change. In 2023, a group of 24 government negotiators will hammer out the details of who should pay into the fund and who should be eligible to get the money. Expect a battle over China’s status and the role of the private sector.

After three meetings this year, the committee will present their findings to Cop28 in the UAE in November.

3. Will rich countries finally meet their $100bn promise?

At the Copenhagen climate talks in 2009, wealthy countries promised to collectively mobilise $100bn of climate finance a year to poorer countries by 2020. Official OECD data published last year shows they fell $17bn short, largely because the US did not pay its fair share.

Towards the end of last year, Canadian and German ministers said in a joint report that they were confident the goal would be met in 2023.

Much depends on the US, which has long given a lot less than Europe. The US Congress has proposed allocating just $1bn to international climate finance in the 2023 fiscal year. Can the Biden Administration meet its pledge to scale up to $11.4bn a year through other channels?

4. Will Lula save the Amazon?

After four years of forest destruction under Jair Bolsonaro, Lula Ignacio da Silva took over the Brazilian presidency on 1 January promising to stop deforestation in the Amazon.

To lead on this, he appointed veteran environmentalist Marina Silva as environment minister and indigenous campaigner Sonia Guajajara as indigenous minister. On his first day in office, he reinstated the $1bn Amazon Fund and signed seven executive orders to restore environmental protections.

But with a Congress dominated by Bolsonaro’s rightwing allies, can Lula keep agribusiness and industrialisation of the rainforest in check?

The environmental protection agency Ibama patrols the Amazon (Photo: Vinícius Mendonça/Ibama/Flickr)

5. Will shipping catch up on climate?

Most countries’ climate plans have two big holes in them – international air travel and shipping. These sectors have their own United Nations governing bodies and their own climate discussions.

In 2022, air travel set an “aspirational” net zero by 2050 goal. Shipping is expected to follow suit this year, at a meeting of the International Maritime Organization’s environmental committee in June.

There are more technological options to decarbonise ships than planes. A key debate is whether to aim for true zero or net zero, with the latter leaving wiggle room to use carbon offsets. Other topics up for discussion are whether to set interim emissions reduction targets and how to put a carbon price on shipping emissions.

6. Will there be a clamp down on corporate greenwash?

In November, a UN taskforce put out a strong set of recommendations on what a corporate net zero target should look like. They called out greenwash tactics by Big Oil and financial institutions.

Its chair Catherine McKenna could not have been clearer: “You cannot be a net zero leader while continuing to build or invest in fossil fuel supply.”

So will corporations rise to the challenge, or quietly drop their claims to green leadership? Will organisations like the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero push them to? Will national regulators?

7. Where next for trade treaty reforms?

In 2022, European climate campaigners led an astonishingly successful push against the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), which protects investments in fossil fuels across Europe and Asia.

After years of reform negotiations, the treaty is now in crisis. Several European Union governments are looking to leave, rejecting the green reforms the European Commission negotiated, on the basis they are insufficient.

But the ECT is just one of hundreds of investment treaties which protect fossil fuel investments around the world. Is this the start of a wholesale review of such treaties, or a recipe for chaos?

A demonstration against the Energy Charter Treaty by Friends of the Earth Europe in July 2021 (Pic: Friends of the Earth Europe/Flickr)

8. Will the global methane pledge firm up?

At the end of 2021, over 100 countries promised to collectively reduce their methane emissions by 30% between 2020 and 2030.

Only one major country, Canada, has translated this collective target into a national target. While various governments are moving to regulate methane, including China, which is not a signatory, patchy baseline data and a lack of concrete targets makes accountability challenging.

And Canada, a rich country with plenty of scope to achieve cuts in the oil and gas sector, is only promising 30% – matching the global goal but not leaving any slack for countries with less capacity.

Will governments fully commit to making those cuts, even if it means taking on Big Beef and Big Oil?

9. Will the Montreal deal save forests?

At the Montreal nature talks at the end of 2022, all governments agreed to protect 30% of their land and 30% of their water by 2030.

Several big countries – like India, the US and Canada – have translated that into a national target to protect 30% by 2030. But what does protection mean? Are farmers, loggers and fishers allowed in protected areas? Are indigenous people?

With rich governments unwilling to commit much public money to this agenda, much depends on mobilising funds from private sources and tackling harmful subsidies.

10. Which way will climate votes go?

There are national elections planned this year in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Argentina, Pakistan, Spain, New Zealand and Turkey. It’s a chance for voters to judge Jacinda Ardern’s “fart tax” in New Zealand and Shehbaz Sharif’s response to devastating floods in Pakistan.

In the US, we’ll find out whether Joe Biden, the oldest president ever, is running in 2024 for a second term or make way for a fresh Democratic candidate. On the Republican side, Florida governor Ron de Santis is one to watch, with at least some awareness of the need for climate resilience. Don’t rule out a Donald Trump comeback.

It is also a significant pre-election year for Mexico, one of only two G20 countries without a net zero target. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has backed fossil fuels, is hugely popular but can’t run again – so his blessing will carry a lot of weight. One of the frontrunners is Mexico City mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, a physicist who has promoted rooftop solar and cycle and public transport infrastructure in Mexico City.

Climate scientist Claudia Sheinbaum is in the running to be Mexico’s next president (Photo: Maritza Ríos / Secretaría de Cultura de la Ciudad de México)

11. How will China’s opening up affect the climate?

After widespread protests last month against Xi Jinping’s flagship zero Covid policy, the Chinese authorities abruptly relaxed the rules.

With Chinese people freer to move around, work and buy things, you might expect the economy to grow. But initial signs are that growth is actually slowing further, as medical services struggle under a wave of Covid infections.

The risk is that a beleaguered government will try to restore people’s living standards by any means necessary – clean or dirty. Earlier in the pandemic, officials turned back to polluting heavy industry to stimulate growth. Will this time be different?

12. Who will win Cop28’s fossil fuel fight?

For the second year in a row, this year’s UN climate summit will be held in a member of the gas exporting countries forum – the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

At the last such summit, Cop27, India proposed language to phase out all fossil fuels but was stonewalled by the Egyptian presidency, despite support from a significant minority of countries.

Rather than keep it in the ground, UAE is expected to argue that putting it (carbon) back in the ground can be just as good. Its climate plans rest heavily on carbon capture and storage technology, while expanding oil and gas production.

Will India use its presidency of the G20 to force a confrontation on the issue?

13. Will Europe lock in more gas?

After Russia invaded Ukraine, Europe rapidly sped up its efforts to try and stop using Russian gas. That involved rolling out renewables and heat pumps faster and prolonging the life of some coal power plants.

It also involved replacing Russian pipeline gas with gas shipped in from countries like Qatar and the USA.

But will that be a short-term emergency measure to fill the gap for a year or two before enough renewables are up and running? Or will Europe lock in its dependence on gas with expensive new pipelines and shipping terminals?