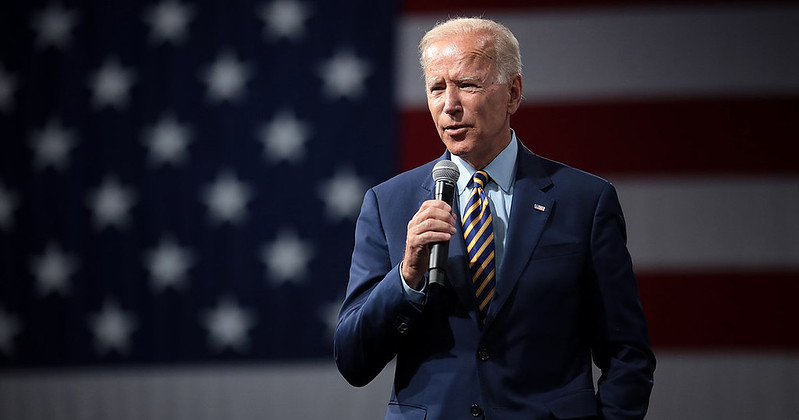

Joe Biden faces a critical test of his climate strategy this week as the US presents its plan to cut emissions this decade and seeks tougher commitments from the biggest emitting nations.

US president Biden has invited 40 world leaders to a virtual summit on Thursday. Invitations have gone out to China’s Xi Jinping, India’s Narendra Modi and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, as well as leaders of some of the world’s most climate vulnerable nations, including prime minister Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh.

The summit has been billed as a moment for the Biden administration to showcase its climate policies and step up global climate ambition after four years of inaction and denial under Donald Trump.

Pete Ogden, of the UN Foundation and a former senior director on climate under Barack Obama, described the summit as “the most anticipated global climate moment since the Paris Agreement” was adopted in 2015.

“This summit is not an end-point, but it is a very important opportunity for re-alignment [with the Paris goals] and to make some real progress. The US and their [2030 climate plan] being a part of that,” he told reporters last week.

US climate envoy John Kerry has been travelling the four corners of the globe to drum up support for the summit. While Japan, South Korea and Canada have indicated they are willing to pledge deeper emissions cuts, Kerry was met with resistance by China and India, while a deal with Brazil on halting deforestation in the Amazon won’t land this week.

Here we outline what announcements and commitments could come out of Biden’s leaders’ summit on climate.

Half way to zero

The US is widely tipped to announce plans to cut its emissions 50% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. This lags behind Europe but could spur other large emitters to raise their game.

UN secretary general Antonio Guterres told Reuters the move “will have very important consequences in relation to Japan, in relation to China, in relation to Russia” and other nations which aren’t on track to halve their emissions.

Japan and Canada are the most likely candidates to join the “50% club” on Thursday, with South Korea tipped to follow later in the year.

Jake Schmidt, managing director of the international programme at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), said all “must rise to the moment” and commit to get halfway to net zero emissions by the end of the decade.

Australian prime minister Scott Morrison, a staunch defender of the coal industry, is not thought to have a strengthened 2030 target up his sleeve.

As the G7 group of rich nations ramp up their ambition in the next few months, Australia risks being left out in the cold, Jennifer Tollman, a senior policy advisor at E3G, told Climate Home.

“Australian citizens will no doubt start to wonder whether their government is acting in their or the fossil industries interest – and to what extent these really are still the same,” she said.

Japanese prime minister Yoshihide Suga is expected to announce a 2030 target of at least 50% at Joe Biden’s climate summit on 22 April CREDIT/Wikimedia Commons

Emerging economies stay silent

A meeting between Kerry and China’s climate envoy Xie Zhenhua in Shanghai provided a ray of hope the world’s two largest emitters could find a way forward to discuss climate action.

In a joint statement issued on Sunday, Beijing confirmed its attendance to this week’s summit and both parties agreed to discuss “concrete actions in the 2020s to reduce emissions”.

China watchers described the statement as a positive step forward, as tensions between Washington and Beijing remain high.

Li Shuo, of Greenpeace East Asia, said the meeting had set the tone for US-China engagement on climate action. “The next big question is what China will do to further its ambition and when it will be announced.” The Boao Asia Forum on Tuesday and the US summit are two key moments for China to outline its short-term plans.

Alongside Beijing, Brazil, South Africa and India (the Basic group) are not expected to bring more ambitious climate targets to the summit.

US climate tsar John Kerry is on friendly terms with Chinese climate envoy Xie Zhenhua, but wider relations between the two superpowers are tense (Photo: US State Department/Flickr)

In a joint statement earlier this month, they said that they had “already set forth climate policies and contributions reflecting their highest possible ambition”.

South Africa is consulting on deepening its 2030 emissions cuts by almost a third compared to its 2015 pledge. Kerry’s visit to India earlier this month did little to shift expectations Delhi would have something new to announce, with both parties simply reaffirming their commitment to rolling out renewable energy.

In Amazon protection talks, US demands action from Bolsonaro

In Brazil, Biden is hoping to strike a deal with president Jair Bolsonaro on protecting the Amazon rainforest. But environment minister Ricardo Salles quashed speculation an agreement could be reached ahead of Thursday’s summit.

“Salles is not where the action is – right now that is sort of a dead end,” David Waskow of the World Resources Institute told Climate Home.

New finance pledges

To convince large developing nations to step up their carbon-cutting nations, rich nations will need to step up their climate aid. The Biden administration is anticipated to set out its international finance commitment package ahead of 27 April and an announcement could be made at the summit.

Climate advocates say the US must set out how it will deliver the $2 billion to the UN-backed Green Climate Fund (GCF) which Trump reneged on in 2016, and increase its contribution in line with other donors.

Biden was criticised last week for offering inadequate support to the GCF after four years of missed payments.

US presidential climate envoy John Kerry meeting Bangladeshi president Sheikh Hasina on a tour of Asia (Pic: ClimateEnvoy/Twitter)

Joe Thwaites, of WRI, told Climate Home that the contribution was not enough to fully restore the US’ credibility on international climate leadership.

“The Biden administration really does seem to get the climate justice argument domestically. And yet I’m not seeing that being carried into its international approach. Does their very good commitment to climate justice end at the border or do they actually recognise that this is an international thing as well?” Thwaites said.

“Scaling up climate finance for developing countries is part of the dynamics that can unlock greater ambition across multiple countries, including the Basic group.”

Pakistan explores debt-for-nature scheme to accelerate its 10 billion tree tsunami

Emerging economies such as India and vulnerable nations have long criticised the US and other rich nations for not meeting their climate finance commitments. There remains an annual $70 billion gap for addressing global climate impacts, UN Environment estimates.

Nisha Krishnan, a climate finance associate at WRI, told reporters last week that “without transparent and credible commitments to increase public climate finance, there will be an uphill struggle to build trust with developing countries that they’re being heard.”

In an executive order signed in February, Biden committed his government to end public funding of ‘carbon-intensive’ fossil fuel projects.

Thwaites told Climate Home that “it would be smart for the US to include this as part of the climate finance plan” and said it could steer federal agencies to start scaling down fossil fuel finance.