One of the world’s most important institutions in the fight against climate change is also one of the UN’s most opaque.

The International Civil Aviation Organisation (Icao), headquartered in downtown Montreal, has been charged with reducing the rising carbon emissions from international flight – an enormous commercial, technical and public relations challenge for the industry.

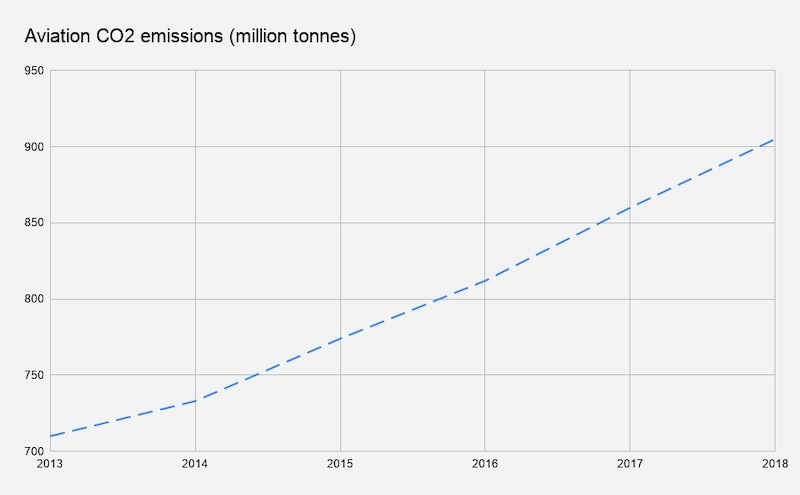

Between 2013 and 2018, aviation sector emissions grew from 710 to 905 million tonnes of CO2, according to the latest estimates by the International Air Transport Association (Iata). Flying now generates just under 3% of global emissions, roughly the same as Germany. Icao’s own forecast anticipates emissions to increase by up to 300% by 2050 under business as usual.

Climate advocates say oversight is critical in a matter of such high public interest. But through interviews with delegates and observers, Climate Home News has found scrutiny is restricted and key information protected by non-disclosure agreements.

While observers find access difficult, industry presence at Icao is the norm. That is partly a legacy of Icao’s origins. Founded in 1944 as a way to use commercial aviation to ensure cooperation and peace-keeping, Icao was created as a forum for cooperation between large aviation countries in an era dominated by flag-carrying airlines. Sensitive commercial data informs some discussions and Icao’s central decision-making has been designed to protect it.

“Meeting behind closed doors to discuss measures to reduce emissions from international aircraft is not acceptable,” said Brice Böhmer, climate governance integrity lead at Transparency International.

“Confidentially is important in a limited number of ways, but not when discussing the environment and climate change,” an NGO source told CHN. CHN has spoken to several sources for this story who asked not to be identified because of the political sensitivities.

In an extreme example of opacity, the body uses a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), seen by Climate Home News, to keep a tight lid on all documents from its committee on aviation environmental protection (Caep) – the body making recommendations on new policies and standards for emissions reduction.

Caep documents are stored on a secure portal and accredited observers can only access the papers if they sign the agreement.

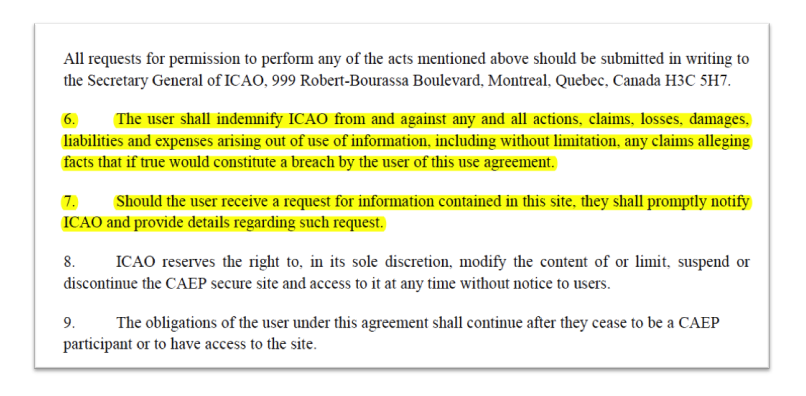

Under the agreement, observers “indemnify Icao from and against any and all actions, claims, losses, damages, liabilities and expenses” arising out of the disclosure of any information provided in the meetings. They do so “without limitation”.

In theory, this means leakers could be made to pay out vast financial claims made by airlines against the UN body as a result of documents becoming public.

Those with access to the portal agree to “promptly notify” Icao if they receive a request to access the information – for example from the media or an NGO – and have to “provide details regarding such request”.

Reports that summarise Caep’s plenary meetings are published and available to buy from Icao for a fee. The 2016 report cost $452.

This “heavy-handed approach” goes “far beyond any other UN agency”, according to a source with knowledge of the Icao negotiations.

UN Climate Change told CHN it doesn’t use non-disclosure agreements.

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) – the UN body that oversees global shipping – referred CHN to documents setting out conditions for observer participation. Although the IMO has also been criticised for its lack of transparency, there is no evidence it uses NDAs.

Legal advisers at Transparency International said that while the NDA wasn’t unusual from a legal perspective, it acted as a deterrent for information to be disclosed.

Böhmer said: “Instead of imposing confidentiality and non-disclosure, all meetings should be public by default. If some information is confidential, it should be noted and explained by justifying why and how it will harm if it was published,” he said, and sensitive parts could be redacted or classified as confidential.

Böhmer added civil society and the media “need to have full access to meetings and documents” in order to ensure accountability and trust in Icao’s capacity to do its share on climate action.

An Icao spokesperson said he was “befuddled” by claims that Icao was not open and that the body “welcomed and encouraged” scrutiny. “Throughout the UN system, closed meetings and restricted documentation facilitate the diplomatic process toward cooperation between sovereign states,” he told CHN, adding that the Icao secretariat “would not be in a position to speculate” why countries decided to restrict access to documents and meetings.

A spokesperson for industry body Iata said: “We do not believe it is necessary for all information and Caep working papers to be made public, but we agree that the availability of final reports and recommendations is important.”

Climate Home News needs your help… We’re an independent news outlet dedicated to the most important global stories. If you can spare even a few dollars each month, it would make a huge difference to us. Our Patreon account is a safe and easy way to support our work.

They added: “If the information used in Caep work was not protected by a non-disclosure agreement, stakeholders would be much more reluctant to share such information and the quality of Caep’s work would suffer from it.”

National delegates from 193 countries are gathering in Montreal later this month for an assembly meeting – Icao’s only public access meeting, which takes place once every three years. At stake in Icao’s negotiations is the integrity of the system being drawn up to green the aviation sector.

Icao member states have agreed an “aspirational goal” to make all growth in international flights after 2020 carbon neutral. Countries have agreed to use a market-based offset mechanism known as Corsia, which is due to launch in January 2021 with a three-year voluntary pilot phase.

Corsia is the primary tool to mitigate emissions from flying. Efficiency improvements are incremental, lagging behind demand growth, while alternative fuels have yet to be developed at scale.

Fourteen offset programmes have so far applied to participate in Corsia. These include the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), an offset scheme developed under the Kyoto Protocol and widely criticised for failing to produce real emissions reduction.

Analysts have previously warned that thousands of old CDM credits could flood the Corsia market, driving the price of credits down without acting as an incentive for further emissions reduction.

Gabriel Labbate, an Icao observer for UN Environment (Unep), said “the environmental integrity of Corsia will decide whether airlines emissions growth will be carbon neutral by 2021 or not”.

Aoife O’Leary, an expert on carbon pricing, aviation and shipping at the Environmental Defense Fund, warned Icao’s lack of transparency failed to inspire public confidence.

“If Corsia is to be successful then the public needs to have faith that the offset criteria are being applied with integrity. If it’s done behind closed doors, nobody is going to have that faith and it could be the downfall of Corsia,” she said, adding: “We know there is quite a lot of lobbying happening in that space.”

While the assembly will vote on progress made over Corsia’s development, key decisions will be made in Icao’s governing body, its council. This includes drawing up the list of offset programmes under Corsia.

Elected by the assembly, the council is constituted of 36 states, including 20 of the world’s largest air travel manufacturing and infrastructure countries.

Some countries such as Brazil and China, both members of the Icao council, are pushing for the CDM scheme to operate under Corsia. India, another council member, has joined them.

A technical advisory body of 19 members has been appointed by the council to make recommendations on which programmes should be included under Corsia by March next year. This includes former chairmen of the CDM executive board, José Domingos Miguez of Brazil and Peer Stiansen of Norway.

The recommendations made by the body to the council won’t be made public, several sources told CHN. It may never be clear whether or not technical advice is adhered to, or whether national or industry interests overrule some aspects.

Council meetings are also effectively closed to observers and all working documents kept on a secure portal.

Icao’s rules of procedure state most meetings “shall be open to the public”, but observers need to be signed into the building by a council member – making the headquarters’ front door the first hurdle for transparency.

In practice, an industry source told CHN, the largest trade groups representing global manufacturers, airlines, airports and navigation services providers are usually allowed to enter, but NGO observers are barred.

Icao said the public was able to attend council sessions physically when seats were available and the meetings hadn’t been declared closed, adding that information from the meeting was “of course available on request”. But when CHN requested a list of participants at its last council meeting, Icao refused, saying it was closed.

Observer participation in Icao’s environmental protection committee is also heavily restricted. Labbate told CHN that when Unep decided to join the talks as an observer it took a whole year and two requests from its then executive director to obtain permission.

Six trade associations and lobby groups are accredited as observers to the meetings, according to participants lists dated between 2010 and 2019 obtained by CHN. NGOs are permitted to attend the meetings under a single observer delegation, the International Coalition for Sustainable Aviation.

CHN found several examples of industry officials listed as advisers among state delegations at Caep meetings. At the last February meeting, this included Annouck Barreaux, from the French aerospace trade association Gifas, and the secretary general of the Union of Aviation Industrialists of Russia Liudmila Rostovtseva.

The industry insider told CHN the industry was not against environmental regulation. In the face of mounting public concern, including the flight shaming movement, the source said green rules were essential to the sector’s “licence to grow”.

Ahead of the assembly meeting in Montreal, industry lobbies coordinated by the Air Transport Action Group (Atag) called on Icao to develop a long-term emission reduction goal for the sector, pointing to existing industry commitments to halve emissions from 2005 levels by 2050 – a call long backed by NGOs.

The spokesperson for Iata said: “We think more public information could be beneficial, but at the same time we understand that the discussions in the council would also be even more politicised if everything was publicised. The challenge is finding the right balance between ensuring an effective dialogue in the Council and transparency.”

An Atag spokesperson said: “One could argue that these discussions are able to proceed more quickly, as they can be more technical in nature, rather than a political show, as we see in other fora [such as UN Climate Change].”

The spokesperson defended the presence of industry representatives in government delegations, saying they were important for giving technical input into the process which was “primarily developing standards on aviation safety and there is no reason why you would want to avoid expertise from being input in such discussions”.

Main photo from Deposit Photo.