On 20 January, a day which is far too dry for the season, Mounir Kadri takes stock at the foot of one of his date palms. “This year is a complete disaster. Last year, I managed to sell my harvest for 12,000 Tunisian dinars ($4,200). This year, because of the drought and diseases, I could only sell it for 4,000 dinars ($1,400)”, he says.

Mounir relies on dates for his livelihood, like nearly half of Tozeur’s inhabitants. This oasis – over 4,000 years old – is the largest in Tunisia. Located at the edge of the Sahara, in the southwest of the country, the city wants to be “top of the class” for environmental management and aspires to energy autonomy.

Approximately 97% of Tunisia’s electricity is generated from fossil fuels, mainly methane gas. In 2020, nearly 57% of the country’s gas needs were met through imports, mainly from Algeria.

The country aims to produce 30% of its electricity from renewables – hydro, solar and wind power – by 2030, according to its updated national climate plan. If it reaches that goal, national carbon intensity will fall 45% compared to 2010.

To help it achieve its renewables target, Tunisia is installing two public solar plants in Tozeur in March, each with an output of 10 MW. The project was financed by the German Development Bank (KfW), with €23 million ($26m) of loans repayable over 12 years, plus a €2m ($3m) grant from the EU and KfW allocated to technical assistance and staff training. The solar panels are supplied by two European manufacturers: TerniEnergia from Italy and GenSun from France.

“Nearly 17,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions will be avoided each year compared to before the installation of the solar plant, helping the country to reach its goals in terms of renewable electricity generation,” Abderrazek Al Ouja, the project manager of the solar farm tells Climate Home News. The electricity generated is enough to supply around 40,000 homes.

The farming community of the oasis takes a sceptical view of this installation. In the last two years, the farmers have accumulated 17 million dinars ($6m) in debt by pumping groundwater and the Tunisian Electricity and Gas Company (STEG) is now threatening to cut off their electricity.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; }

/* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Water scarcity is a problem across Tunisia and access to water is the number one issue for farmers in Tozeur. They face soaring electricity bills to irrigate their date palms from rapidly depleting groundwater sources.

“We now need electricity to pump our water. And it doesn’t seem like this new solar plant will help us with our electricity problems, as no one has consulted us until now,” says Mohamed Jhimi, farmer and president of an agricultural development group in Tozeur.

“They’ve got some nerve to implement a solar power plant, without it being planned to benefit those who suffer the most here,” says Jhimi.

Mohamed Jhimi, president of an agricultural development group in Tozeur, says local farmers are facing mounting debts and water shortages (All photos: Aida Delpuech)

For Hamza Hamouchene, a just transition expert and researcher at the Transnational Institute (TNI) in the Netherlands, “this kind of project usually exacerbates already existing problems”.

“The local communities already suffered from huge water poverty, as the water levels are very low. Since the installation of this mega solar plant… some of the water has been diverted to go to this solar farm,” he tells Climate Home News.

The entire process is centralised and financed through development banks, he says. “They do the so-called social assessments but in reality, they are just ticking boxes.”

Tunisia emits only 0.07% of global greenhouse gas emissions and the country is among the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. “With the creation of this solar park, the Tunisian state misses the opportunity to address the climate issue as it unfolds here,” says Salem Ben Slama, a member of the local association La Ruche. “We have invested millions of dinars in a mitigation programme, that is the solar farm, but those who suffer the full force of climate change here, the farmers, are ignored.”

This imbalance is reflected in the figures. In its climate plan, Tunisia outlines that aims to spend 74% of its climate budget, $14.3 billion, on cutting or preventing emissions, compared to $4.3 billion on adapting to the impacts of climate change. For the energy sector, the country mainly aims to focus on the development of solar energy, multiplying its production capacity tenfold by 2030, compared to 2020.

“What we need is a national programme to protect and value our fragile ecosystems, as well as our indigenous and local knowledge,” says Ben Slama. With their worsening working conditions, more and more farmers are forced to leave their land and knowledge behind.

To help communities adapt to climate impacts, the assembly of Maghrebi citizens for the oasis of Tozeur has called for “the promotion of technology transfer and the strengthening of knowledge in the field of adaptation”. They stress the importance of improving scientific knowledge around how climate impacts affect oases.

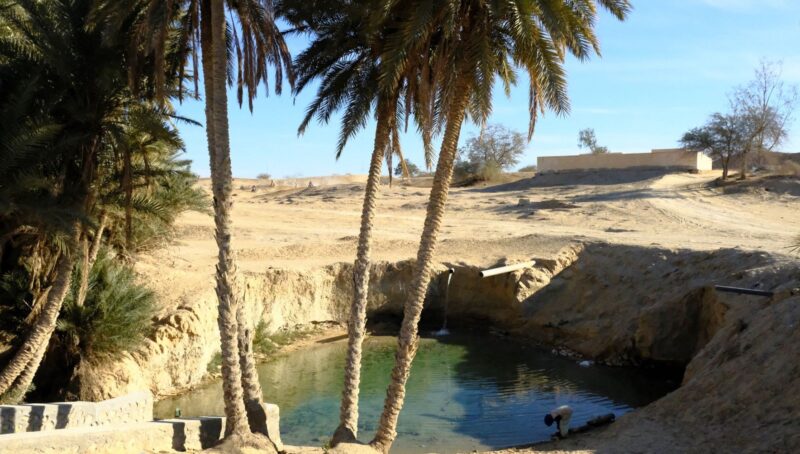

The source of Ras el Ain once irrigated the entire oasis. Today it is dry, because of agricultural intensification and construction

Oases are among the most fragile ecosystems on the planet. In Tozeur, the past two years were the worst ever recorded for farmers, who rely almost entirely on date production. In Tozeur, almost 50% of the population works in date production, according to Karem Dessy, president of the Association to Safeguard the Medina of Tozeur.

“Most of our current problems are of climate change,” says Karim Kadri, an engineer and researcher in oasis agriculture in Tozeur. Over the past two years, temperatures have reached record highs – almost 50C in the shade in summer – while rainfall has been at its lowest.

These conditions allowed a devastating disease called “boufaroua” to attack the palm trees. “These are mites that grow around the fruit and suffocate them,” explains Kadri. The dates turn white and the whole crop is destroyed. “Usually, it only takes one or two rains to wash our trees and naturally rid them of these invaders,” he says.

Oasis is synonymous with water. In addition to the rainwater, the groundwater is also drying up. Previously, a single source, that of Ras El Ain, was used to irrigate the entire oasis of Tozeur. The water was distributed among farmers through an irrigation system dating back to the 13th Century.

“But in the 1990s, these water tables began to be depleted when the state expanded the oasis with farms established, as well as with the development of the hotel zone. It was the beginning of irrigated areas and drilling practices to extract water in larger quantities,” says Chaker Bardoula, a farmer and former president of the regional federation of agriculture.

View of the oasis of Tozeur from Ras el Ain. This area used to be covered by vegetation before water sources were depleted

Today the naturally available water resources no longer exist. Faced with the disappearance of this “mother-source”, the Tunisian state has drilled boreholes and farmers have installed their own pumps.

“It is these pumps that are very expensive for electricity,” says Ben Slama. “It is a huge problem.” Since the 1970s, the cost of electricity has increased four to six times, he says. While costs rise, farmers are under pressure from middlemen. “They are taking advantage of the Covid pandemic to force farmers to lower their selling prices. They smash prices and no one is monitoring”, says Chaker Bardoula.

All these pressures mean that farmers have been unable to pay their electricity bills for the past two years. “We are suffocating: on the one hand because of climate change, on the other because of our debt to the STEG,” says Jhimi.

Ben Slama said that as long as no system of subsidising electricity for farmers has been found, it is impossible to speak of social responsibility.

“This plant does not address local communities. We have been excluded from this project, no one has come to consult us,” he says.

A pile of dates attacked by mites. This year, a big part of the harvest was lost, because of climate impacts

Taha Sendid, Tozeur’s STEG district manager, says the company has been helping the farmers by setting up payments by instalments, to resolve the long-standing debt issue. “If they have specific issues, they should address [them to] the State,” he says.

For Hamouchene, “one way of making this transition ‘just’ would be to cancel these farmers’ debts and provide them with cheap electricity”. State subsidies could also put a brake on individual drilling initiatives, he says. Many farmers, because of a lack of assistance, dig wells that are too deep, weakening the water table even more.

To protect what is left of the oasis, Dessy says the government must urgently invest in adaptation solutions to use less water. “At this pace, we only have a hundred years before the water resources completely vanish, according to local hydrogeologists. We need to act fast.”

This article is part of a climate justice reporting programme supported by the Climate Justice Resilience Fund. Main image: Aida Delpuech.