The host of this month’s penultimate round of talks to agree a global treaty on tackling plastic pollution is concerned that certain countries “seem to have forgotten” that all nations originally backed an ambitious pact.

Canadian Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault, who will host the talks in Ottawa starting on April 23, said in an interview with Climate Home that all governments had “agreed collectively that we wanted an ambitious treaty to fight plastic pollution and to eliminate it by 2040”.

But, he added, “unfortunately some countries seem to have forgotten that’s what we agreed upon [at the United Nations Environment Assembly] almost two years ago. I’m going to make it my mission in life in the coming weeks to remind everyone that this is our collective agreement.”

He did not specify which countries appear to be backtracking, but noted that some “are in more of a hurry than others” to get a deal – “which is why you have a high-ambition coalition”.

That coalition is pushing for a strong accord to end plastic pollution and includes all large developed countries except the United States, plus some developing nations.

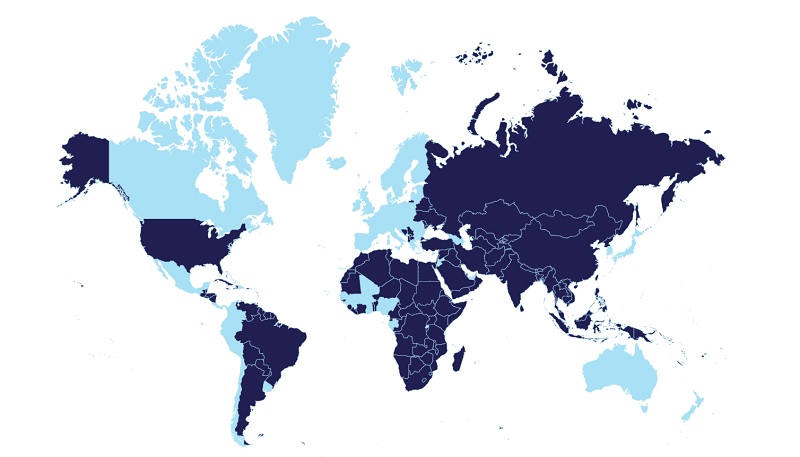

The members of the self-described “high-ambition coalition” are coloured in light blue.

Guilbeault was speaking during the latest UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi last month, where some governments tried to water down anti-plastics language.

David Azoulay, from the Center for International Environmental Law, told Climate Home “a number of countries” had tried at this year’s UNEA to “get around or away” from the mandate to set up a plastics treaty.

They did not propose a rival resolution, he said, “probably because they saw there was very little appetite for it”. But that did not stop them from attempting to use the assembly to influence the plastics treaty negotiations, he added. The talks are organised by the United Nations Environment Programme.

In submissions to the UNEA, the US tried to delete the words “legally binding” in reference to the plastics treaty, Iran wanted to remove “ambitious”, and Saudi Arabia attempted to cut a reference to accelerating the treaty talks.

Russia’s ambassador to Kenya, Dmitry Maksimychev, told the UNEA that Russia is an “active participant” in the talks and “we do not support shifting emphasis to restrictive measures of a productive or commercial nature”.

Plastics support fossil fuel demand

Over the last two years, government negotiators have gathered for three rounds of talks on setting up the treaty to tackle plastic pollution.

The fourth round will be held in Ottawa this month, and the fifth and supposedly final session will be in the South Korean city of Busan in November. The agreement should then be adopted officially at a diplomatic conference in 2025.

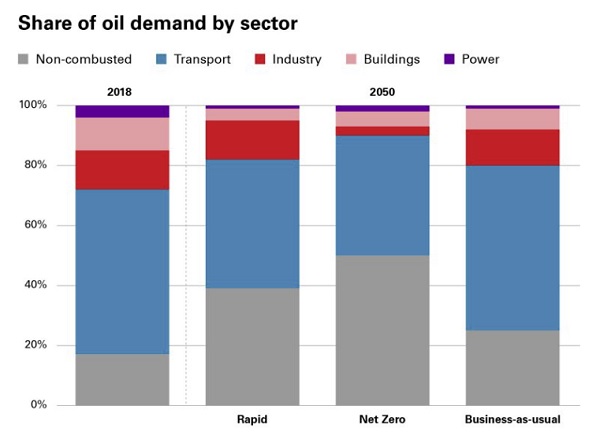

BP expects the share of oil demand from non-combusted (grey) sectors like plastic to rise in the next few decades. (Photo: BP/Screenshot)

Plastics are made from oil and gas, and their production causes 3% of greenhouse gas emissions. The fossil fuel industry predicts that as demand for oil and gas for energy falls, they can make up for it by selling their products to plastic manufacturers.

New estimates from the US-based Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory show plastic production emits as much carbon pollution each year (2.24 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2019) as 600 coal-fired power plants.

A study published by the lab on Thursday, supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Beyond Petrochemicals campaign, warned that carbon pollution from plastic production could triple by 2050.

And even if global power grids shift over to clean energy, the plastic industry’s share of the global carbon budget could rise from just over 5 percent now to more than 20 percent by mid-century, based on conservative projections for industry growth, it added.

Plastic litter also makes flooding – already exacerbated by climate change – worse.

In Zambia, Lwenga Mulela, whose company converts plastic waste into useful products like paving and plant pots, told Climate Home plastic bottles pile up in drainage channels in the nearby capital Lusaka and stop rain escaping down the drain, causing flooding on the streets.

Lwenga Mulela shows plastic wrappers which she turns into products like paving on March 12 24. (Photo: Joe Lo)

During a brief rainstorm in Lusaka’s Central Business District in March, Climate Home saw cars slowing to a crawl to pass through puddles and pedestrians jumping over water to stay dry.

Money talks

The UN treaty negotiations have so far been divided on whether to focus on the production of plastic, potentially through targets to reduce it, as the “high-ambition coalition” and climate campaigners want.

The alternative is to limit its scope to expanding recycling of plastic, as the industry itself and the US, Saudi Arabia and others are calling for.

Asked if plastic production should be in the treaty, Canada’s Guilbeault said: “We have to look at every element of plastic pollution.” But asked about the biggest remaining divides, he pointed to finance.

Many countries, particularly small islands, “receive an incredible amount of plastic pollution that they’re not responsible for, and there should be an international mechanism to help them deal with the problem,” he said.

Activists clean up a beach in Fiji in 2016 (Photo: Kurt Peterson/Greenpeace)

“Right now with the economic situation internationally – high interest rates, high inflation – it’s a difficult conversation but it’s a necessary conversation nonetheless,” he added.

This was highlighted by Madagascar’s representative at the UNEA who said his country backed a plastics treaty and was “insisting on the need to prepare global countries of the south and support them in this regard”.

In Zambia, entrepreneur Mulela also called for finance for developing countries to develop waste disposal and recycling systems. She said the companies that produce the plastic should provide that funding, as should richer nations.

“I think they have an obligation,” she said. “It’s a global village, so what is affecting one part of the world is also affecting every other part of the world.”

Approval by consensus or vote?

If governments do not unanimously agree on a text in November, a treaty could be endorsed through a two-thirds majority vote – but, for many negotiators, that would be a last resort.

Jyoti Mathur-Filipp, head of the secretariat responsible for the talks, told Climate Home “there is no wish on any member state’s part to actually have a vote on substance… so for us, we hope that we will adopt this treaty with consensus, without a vote.”

But, for campaigners like Greenpeace’s Graham Forbes, the apparent unwillingness to vote could end up weakening or delaying the treaty as he argued that a process based on consensus has enabled low-ambition countries to “undermine substantive progress”.

“Voting would enable member states that are serious about addressing the issue to negotiate a treaty that actually gets at the core of the issue: reducing plastic production and use,” he said.

Guilbeault took the middle-ground, noting that not every country has to agree to something for it to be adopted by consensus.

He wants the new treaty “to have as much buy-in as possible from as many countries as possible but, at the same time, I don’t think the world should be held hostage to the interest of a few countries – that’s not consensus either.”

The talks in Ottawa are tasked with narrowing down the draft text for the treaty. Guilbeault said he hopes to see 75-80% of it agreed this month, but added that the thorniest issues will be left to Busan in November.

(Reporting by Joe Lo; editing by Megan Rowling)

This article was amended on April 23, 2024 to clarify that Steven Guilbeault is the host of the plastics treaty talks in Ottawa – not the chair, as previously stated. The role of chair is currently held by Luis Vayas Valdivieso, Ecuador’s ambassador to the UK.