Governments around the world share two problems right now: climate change and soaring energy prices. Investment in renewables and in energy efficiency are commonly and rightly touted as a solution to both. A third solution, known as “demand response”, gets less attention.

Citizens want enough electricity to keep the lights on and governments have tried to give them that by supplying enough electricity to meet demand. But people’s demand for electricity is not constant, it goes up and down throughout a day and throughout the year.

In richer countries, many people fire up their air conditioning, switch on their lights and plug in their electric vehicle when they get back from work. After dinner, they turn on their dishwasher and they open the fridge during the advert break for Game of Thrones.

Governments have to provide enough electricity to meet not just the average electricity use but the peak electricity use – half-time in the Superbowl on a boiling hot day. This is when grid operators call on the dirtiest, least efficient and most expensive generators.

When a heatwave hit Europe recently and spiked air conditioning use, for example, the UK’s grid operator paid 5,000% more than usual to import electricity.

Flattening those peaks, by getting people to shift electricity use to periods of low demand, makes the whole system cheaper, cleaner and more reliable.

That doesn’t work for every application. Nobody wants to watch television at 3am or run their air conditioning when it’s cold. But people can run their dishwashers and washing machines at night-time. Industrial customers like aluminium smelters can be flexible with their electricity use too.

What’s it got to do with climate change?

For the next few decades, electricity will be supplied by a mix of clean electricity and dirty electricity. Grid operators will use the clean electricity when they can and fossil fuel-powered electricity when that doesn’t fully cover demand.

California gets most of its electricity from zero-carbon sources, but it is building gas generators for backup. The less demand outstrips supply of renewables, the less gas it will burn.

Importantly, according to Brattle Group analyst Ryan Hledik, demand response will make electrification and decarbonisation cheaper. If you can charge up your electric vehicle with cheap electricity at night rather than expensive electricity at 6pm, you are more likely to tell a friend to swap their gas-guzzler for an electric vehicle.

In many parts of the developing world, there’s not enough electricity to go around even before electric vehicles and electric heat pumps are rolled out. So, as countries develop and electrify homes and transport, demand response can make that power go further.

How does demand response work?

The simplest way to encourage consumers to shift their electricity use is to put them on time-of-use tariffs. This works like off-peak fares on public transport or happy hours at a bar, encouraging customers who can shift their demand to do so.

Today, these rates are typically targeted at electricity-guzzling businesses rather than households, as this is where they can have the most impact for the least outreach work.

Hledik says that demand response is most advanced in North America. In the Canadian province of Ontario, for example, electricity costs different amounts at different times of the day. Andrew Dow, from Ontario’s grid operator IESO, said it’s cheaper at night because it’s not being used as much.

Big electricity users pay their electricity bills proportionately to their use in the five highest demand hours of the year. “So these businesses are incentivised to monitor electricity demand throughout the year and, when they see something that could be one of the top five peaks of the year, businesses are incentivised to reduce their use,” Dow explained.

A dispatcher works at Texas’s grid operator Electric Reliability Council of Texas (Photo: Dpysh w/Wikimedia Commons)

South Africa takes similar measures. Malcom Van Harte works for their grid operator Eskom. He told Climate Home that 22 large industrial electricity customers are incentivised to shift their peaks with time-of-use tariffs.

A twist on time-of-use is that major users are asked to switch off 10-20% of their electricity when demand looks like outstripping supply. If they accept this request, the customer is then exempted from the planned outages which plague South Africa, known as “load shedding”.

Particularly in North America, households are getting in on the act, Hledik said. “Some utilities have now made time-of-use the default residential rate,” he said.

In the US state of Vermont, a utility called Green Mountain Power is deploying Tesla Powerwall batteries to people’s homes. Most of the year, the resident gets to use this battery as a backup generator, to absorb excess power from their solar panels or to reduce their bill on a time-of-use rate. But, for the few days a year when Green Mountain Power is desperate for electricity, it can take control of the battery and feed that stored electricity back to the grid. “It’s a win-win situation”, said Hledik.

In future, electricity users could even be paid to discharge their vehicle’s battery to the grid at peak times. This is known as vehicle-to-grid power and, Hledik said, is still at the pilot phase. “It’s still very much at a point where the technology and the commercial business case are being tested and proven,” he said, “whereas the simpler time-of-use rate concept is something that’s available at scale.”

How will the energy transition affect demand response?

As electricity systems become increasingly based on renewables, daily and seasonal patterns of supply will shift. Conventional power plants can pump out electricity 24/7 and 365, as long as they have a supply of fossil fuels. But the sun and wind come and go.

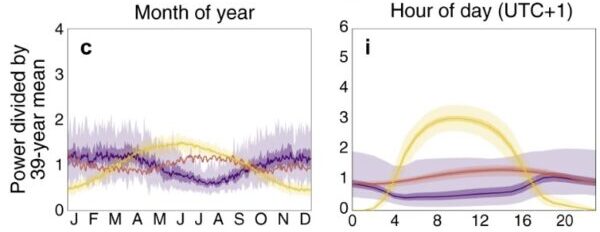

The first chart shows wind (purple) and solar (yellow) potential vs demand (orange) throughout the year in the US. The second shows the same but throughout a summer’s day in the US. (Tong et al)

The same figures as above, but for South Africa, which has southern hemisphere seasons

Hledik said that parts of the US with high solar deployment like California and Arizona are already seeing this shift. Previously, grid operators tried to delay electricity use from the post-work peak of 6pm to after 8pm.

Now they have more electricity than they need between midday and 2pm when the sun is at its highest, so that’s the best time of day to run dishwashers and washing machines.

In an emergency, consumers have proved willing to temporarily cut consumption without price incentives. When an extreme heatwave and demand for air conditioning put a strain on the Californian grid in early September, grid operators sent a text alert asking residents to conserve energy. Within five minutes, usage fell by 1.2GW, averting blackouts.

European countries will increasingly be reaching for such tools, as flattening peak demand forms part of Brussels’ plan to cope with reduced Russian gas imports.

This article is the third in a four-part series on the future of energy.