The Greenland ice sheet is losing mass seven times faster than in the 1990s, according to new research.

In a paper published today in Nature, an international team of 89 polar scientists, working in collaboration with ESA and NASA, have produced the most complete picture of Greenland ice loss to date.

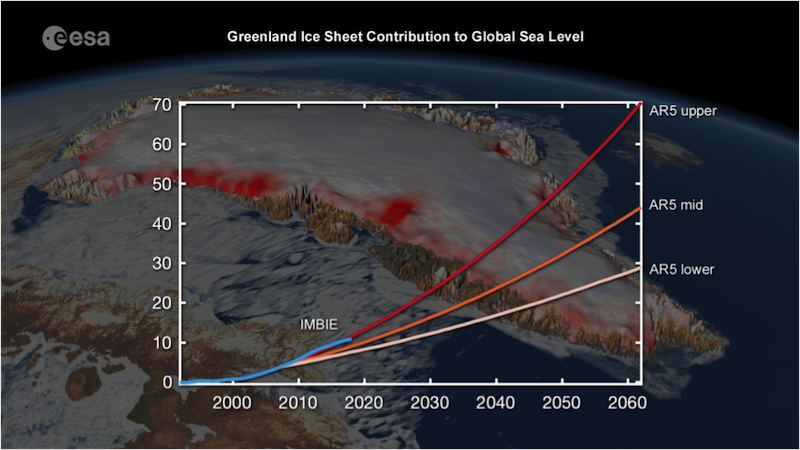

They estimate that Greenland lost 3.8 trillion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2018 – enough to push global sea levels up to 10.6 millimetres. Over the study period, the rate of ice loss was found to have increased seven-fold from 33 billion tonnes per year 1990s to 254 billion tonnes per year in the last decade.

The Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise (IMBIE), led by Professor Andrew Shepherd from the University of Leeds and Dr. Erik Ivins at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, compared and combined data from 11 satellites – including ESA’s ERS-1, ERS-2, Envisat and Cryosat missions, as well as the Copernicus Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 missions – to monitor changes in the ice sheet’s volume, flow and gravity.

Using observation data spanning three decades, the team has produced a single estimate of Greenland’s net gain or loss of ice, known as mass balance.

Previous satellite-based studies describe Greenland and Antarctica ice sheet losses and their contribution to global sea-level rise over recent decades. This study condenses the available data and provides a consensus view regarding Greenland’s ice loss – enabling more accurate projections of future sea rise to be made.

And, with coastal areas being some of the most densely populated areas on the planet, the findings will aid communities to prepare, while also illustrating the urgent need for the international community to curtail greenhouse gas emissions.

In its last major assessment, the IPCC’s central climate warming scenario predicts a 60 centimetre rise in global sea levels by 2100, putting 260 million people at risk of annual coastal flooding. The faster-than-expected rate reported by the IMBIE team shows that ice loss is following the IPCC’s high-end climate warming scenario, which predicts sea level will rise by an additional seven centimetres.

Professor Shepherd explains, “As a rule of thumb, for every centimetre rise in global sea level, another six million people are exposed to coastal flooding around the planet. On these current trends, Greenland ice melting will cause 100 million people to be flooded each year by the end of the century – so 400 million in total due to all sea level rise.

“These are not unlikely events or small impacts: they are happening and will be devastating for coastal communities.”

Using satellite observations in combination with regional climate models, the team show that just over half of the losses were because of increased surface meltwater runoff, driven by warming air temperatures. The remaining losses were the result of increased glacier flow triggered by rising ocean temperatures.

Ice losses reached a peak of 335 billion tonnes per year in 2011, a trend that has reversed since, dropping to an average of 238 billion tonnes per year through to 2018 – but remaining seven times higher than observed during the 1990s.

Professor Shepherd comments, “The variable nature of the ice losses from Greenland over the three decades is a consequence of the wide range of physical processes affecting different sectors of the ice sheet and reflects the value of monitoring year-to-year fluctuations when attempting to close the global sea level budget.”

ESA’s Director of Earth Observation Programmes, Josef Aschbacher, adds, “The findings reported by IMBIE illustrate the fundamental importance of satellites to monitor the evolution of ice sheets, and for evaluating and refining the models used to predict how climate change could affect the future evolution of ice sheets and sea level rise.

“Greenhouse gas emissions are still going up, not down. We are leaving future generations to be confronted with increasingly severe impacts of climate change, such as rising sea levels. By taking the pulse of the planet, ESA is highlighting the changes occurring across the planet and the need to redouble efforts to meet the internationally agreed goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C over pre-industrial levels.”

IMBIE is supported by ESA Climate Change Initiative, which generates accurate and long-term satellite-derived datasets for 21 Essential Climate Variables, to characterize the evolution of the Earth system.

This post was sponsored by the European Space Agency. See our editorial guidelines for what this means.