The 2015 Paris Agreement became the most important climate accord of its decade by encompassing and embracing different circumstances and capacities around the world.

But with that broad accommodation came the challenge of crafting a single set of rules for all to follow. That tension was clearly on display in Katowice in December, as the UN climate talks dragged more than 24 hours beyond their scheduled close before finally failing to resolve differences over how carbon markets will be governed.

While the PA avoids mention of ‘markets’, its Article 6 seeks to clarify how ‘mitigation outcomes’ can be transferred from one country to another. This becomes complicated. Markets are a primary facilitator of such transfers, and ‘mitigation outcomes’ is a euphemism for carbon credits.

As it happened: Final scramble for deal at climate talks in Poland

In a carbon market, regulators set caps for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across a segment of the economy, and distribute credits to covered entities that are based on their individual GHG reduction obligations. These entities then have the option of lowering their own emissions and selling these credits, or purchasing credits on the market to cover their excesses.

As regulators progressively lower the GHG caps, overall emissions decline while individual flexibility continues. Such markets have demonstrated the ability to reduce emissions at lower costs and faster speeds than other approaches, but they remain divisive as a core tool for addressing climate change.

Some question their distributional impacts, and fear that they will lead to emitting activities and environmental stress moving to places where they will continue to impact marginalized communities. Others point out that policymakers often struggle to set emissions caps low enough to make a meaningful difference. Still others say carbon prices are fine in theory but not as impactful as other policy tools – from financial incentives like feed-in-tariffs and subsidies on the one hand to direct regulations like vehicle and factory emissions standards on the other. And that is just in domestic contexts.

Global issues need global coverage

CHN is dedicated to bringing you the best climate reporting from around the world. It’s a huge job and we need your help.

Through our Patreon account you can give as little or as much as you like to support our work. It’s safe and easy to sign up.

Even those who champion carbon markets can challenge the value of exchanging carbon credits across international borders. Such exchanges require context-specific respect for varied national circumstances, how the markets integrate with one another, and – vitally – how accounting systems should be designed to ensure a ton of GHG reduction in one place equals a ton in another.

And so carbon markets became a primary sticking point at Cop24. Like the national climate plans steering them, carbon markets are highly differentiated across different countries. Crafting cohesive policies for emissions trading comes into conflict with the desires of countries to operate as they see fit, and report back to the international community in the manner they choose.

At Cop24, this came to a head in the form a spoiler. Article 6 calls on countries to make ‘corresponding adjustments’ to their domestic emissions inventories to reflect international trades. Plainly, this means not crediting oneself with an emissions reduction that one also sells to another. Such double-counting would erode confidence in the mitigation value of international credits, and send dubious signals to private sector market practitioners.

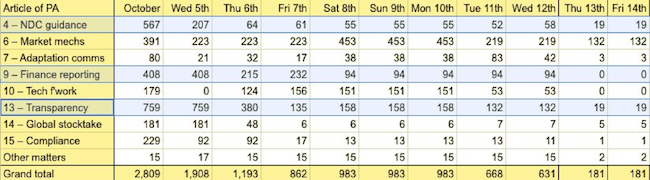

Brazil sought to soften accountability standards for exporting carbon credits, and yield a system where double-counting risks were significantly higher. The international community recoiled, leading to a pervasive impasse on Article 6 as other contentious issues made progress (see table). It was ultimately tabled for further negotiation in the coming year.

Undecided ‘Bracketed’ Clauses by Issue and Date at Cop24

The table above shows progress on articles of the Paris Agreement over the course of Cop24. Article 6 is conspicuous in the continuation of bracketed text throughout the negotiations

(Source: Carbon Brief)

Brazil was the main obstructionist in this instance, but Article 6 will continue suffer the fundamental tension intrinsic to creating a centralized system based on varied commitments and disparate approaches to meeting them. It mirrors wider climate negotiations in being less about finding grand bargains, and more about aggregating activities around the world and providing coherent guidelines for how actions should be measured, reported and verified. The negotiations have become – at their core – an accounting and accountability exercise. The hope for Cop25 is that flexible yet robust rules are agreed upon to work across the range of next generation carbon markets. This was of course the hope for Cop24 as well.

In the meantime trading continues. Countries and businesses can build cooperative markets and let the rule writers “catch up later”. Nothing that happened at Cop24 and no text in the PA prevents markets from operating in the absence of clear international oversight. What Cop24 did reveal is that – for better and worse – the centralized systems of the past are gone, and future efforts will have to reconcile a wider bottom-up/top-down dichotomy to meaningfully contribute to climate mitigation.

Jackson Ewing is a senior fellow at the Duke University Nicholas Institute of Environmental Policy Solutions. A more technical elaboration of this argument can be found here.